The Know

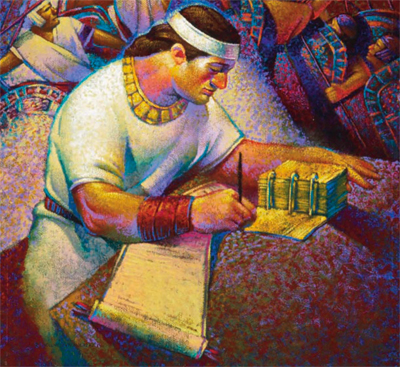

The writers of the Book of Mormon often stated that they would “make a record” of the things that they had seen or done.1 The fact that they said they would “make a record” rather than “write a record” or some other similar phrase may seem insignificant. However, this phrase provides evidence that the writers of the Book of Mormon had training in the ways of ancient scribes.2

The most notable example of this from the Old Testament comes from Ecclesiastes 12:12, in which a young man is warned, “of making many books there is no end.” In his book Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel, Michael Fishbane has pointed out that the reference to “making books” in Ecclesiastes is somewhat unusual.3 One might even assume that this phrase could refer to someone physically making a book or a scroll, rather than the one doing the writing. Thankfully, other ancient Near Eastern texts help to clarify this point.

Some ancient writings composed in a language called Akkadian, record that scribes were expected to “compose” writings.4 The word translated as “compose” is a slight variation on the word “make.”5 Thus, when these scribes were literally being asked to “make a record” they were simply being asked to write a book.6 Fishbane has argued that the unusual phrase “making books” as found in Ecclesiastes is a result of the influence of ancient Near Eastern scribal culture on the person who wrote those verses of Ecclesiastes.7

This technical term, known by scribes throughout the ancient Near East, was used by Aramaic-speaking Jews in Egypt as well, showing that it was fairly widespread.8 Nephi’s use of this phrase fits well with what we know about scribes in the ancient world and suggests that he similarly had training in ancient scribal practices.

This idea is strengthened by the use of the word “abridgement” in the Book of Mormon.9 Ecclesiastes 12:9, a nearby verse that also describes ancient scribal practices, states that “the preacher ... set in order many proverbs.” The phrase “set in order” is a translation of a single word that means “to edit” or “to arrange,” or in other words, “to abridge.”10 This phrase was also commonly used by scribes in the ancient Near East.11 The fact that references to making a record and abridging texts occur next to each other in a section of Ecclesiastes that refers to scribal practices shows that these terms were almost certain technical scribal terms. The Book of Mormon’s use of these terms in a similar way suggests that Nephi had training in the ancient scribal practices known from the ancient world.

However, the use of these phrases throughout the Book of Mormon suggests something else as well. The fact that the phrase is used throughout the Book of Mormon, from 1 Nephi through Ether, suggests that the Book of Mormon authors were careful to pass down this ancient scribal learning from generation to generation.

The Why

Because these details of ancient Near Eastern scribal training were unknown at the time the Book of Mormon was published, these small points serve as evidence for its authenticity. Nephi’s scribal training, which he inadvertently reveals to us through his use of language, tells us something else as well. In 1 Nephi, Nephi used phraseology that was common among ancient Near Eastern scribes. These technical scribal terms come from a much older and broader tradition than just ancient Israel. And yet, Nephi internalized these terms, passed down to him from others, and passed on his scribal learning to the next generation, who continued to use these terms.

References to “making a record” appear throughout the Book of Mormon, showing that later writers valued this scribal education just as Nephi had.12 This careful preservation of tradition is a valuable lesson for us today. Just as Nephi carefully preserved and passed down his learning to others, who in turn carefully preserved and passed it down as well, we can also seek out learning and pass it down to others.13Whether our knowledge is secular or religious, we can do our best to acquire knowledge and then to share it with those around us, like Nephi did.14

Our commitment to learning both spiritual and secular truths, and sharing those truths with those around us, will help us to make the world a better place.15 Acting on this commitment may change the lives of people for generations to come, just as the consequences of Nephi’s carefully acquired scribal training, the Book of Mormon, is still changing lives today.

Further Reading

Anita Wells, “Bare Record: The Nephite Archivist, The Record of Records, and the Book of Mormon Provenance,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 102–106.

Taylor Halverson, “Reading 1 Nephi with Wisdom,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 279–293.

Brant A. Gardner, “Nephi as Scribe,” Mormon Studies Review 23, no. 1 (2011): 46.

- 1. See, for example, 1 Nephi 1:1–2; 19:4, 3 Nephi 5:4-18, Mormon 1:1, Mormon 2:17, Ether 13:14.

- 2. For more on Nephi’s scribal training, see Brant A. Gardner, “Nephi as Scribe,” Mormon Studies Review 23, no. 1 (2011): 46. See also, Anita Wells, “Bare Record: The Nephite Archivist, The Record of Records, and the Book of Mormon Provenance,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 102–106.

- 3. Michael A. Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1985), 31.

- 4. Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 31.

- 5. Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 31.

- 6. Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 31.

- 7. Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 31.

- 8. Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 31.

- 9. Some version of the word “abridge” occurs on the Title Page, 1 Nephi 1:17, Words of Mormon 1:3, Mormon 5:9, and Moroni 1:1

- 10. Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 32.

- 11. Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 32.

- 12. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Nephi Work So Hard to Preserve the Wisdom He Had Received? (1 Nephi 6:5–6),” KnoWhy 262 (January 16, 2017).

- 13. See Taylor Halverson, “Reading 1 Nephi with Wisdom,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 279–293.

- 14. See Book of Mormon Central, “Acquiring Spiritual Knowledge: Act In Faith (1 Nephi 2:16),” KnoWhy 260 (January 11, 2017).

- 15. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Is It Good to Seek Both Spiritual and Secular Learning? (1 Nephi 1:1),” KnoWhy 324 (June 9, 2017).