The Know

The book of Mosiah begins rather abruptly. Unlike the other books in the Book of Mormon, the book of Mosiah does not begin by introducing a speaker or author/editor but, instead, oddly jumps right into the details of King Benjamin’s peace and preparations to crown his son Mosiah as king.1 After a few final verses in Words of Mormon 1:13–18, the book of Mosiah begins:

“And now there was no more contention in all the land of Zarahemla, among all the people who belonged to king Benjamin, so that king Benjamin had continual peace all the remainder of his days. . . . And it came to pass that after king Benjamin had made an end of teaching his sons, that he waxed old, and he saw that he must very soon go the way of all the earth; therefore, he thought it expedient that he should confer the kingdom upon one of his sons” (Mosiah 1:1, 9).

Mosiah was chosen to succeed his father as king, and so a proclamation was ordered “throughout all this land among all this people, or the people of Zarahemla, and the people of Mosiah who dwell in the land, that thereby they may be gathered together” (Mosiah 1:10).

At this public gathering Mosiah was to be declared king (Mosiah 1:10), and also at this gathering Benjamin gave his unforgettable and masterful speech that touched on the atonement, the importance of balancing justice and mercy, the nature of God, and other crucial gospel teachings (Mosiah 2–6). For his part, Mosiah reigned as a righteous king who followed the inspired teachings of his father. “And it came to pass that king Mosiah did walk in the ways of the Lord, and did observe his judgments and his statutes, and did keep his commandments in all things whatsoever he commanded him” (Mosiah 6:6).

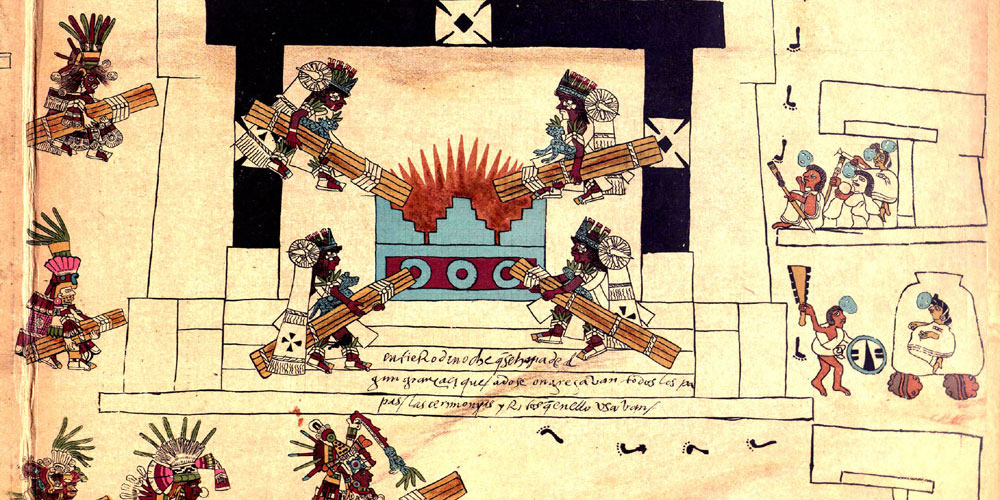

While the doctrinal content of Benjamin’s speech is the most valuable to readers, scholars such as Stephen D. Ricks have noticed that “many features of this coronation ceremony reflect ancient Israelite culture.”2This includes: (1) “the significance of the office of king,” (2) “the coronation ceremony for the new king,” (3) “the order of events reported [which] reflects the ‘treaty/covenant’ pattern well-known in ancient Israel and the ancient Near East,” and (4) “an interrelated cluster of concepts in Israelite religion [that] connects the themes of rising from the dust, enthronement, kingship, and resurrection.”3

As Ricks explores at length, these elements combined to serve something of a dual purpose. On one level, they reinforced the doctrinal underpinnings of the plan of salvation. For example, the theme of rising from the dust can be compared to our mortal journey and resurrection, while enthronement and kingship represent our return to God's presence (cf. Revelation 3:21).

At the same time, they focused the people’s attention on the important fact that the kingship (and by extension the covenantal commitment of the community) was being renewed and perpetuated. The “themes of kingship, covenant-making, rising from the dust, coronation, and resurrection,” all of which are found in Benjamin’s speech, “were closely linked in the minds of ancient Israelites.”4 It is therefore not at all surprising that Benjamin would utilize the opportunity of his son’s coronation to once again teach the fundamentals of the plan of salvation. Much like Jacob did before him, Benjamin couched his discourse in cultural terms and on a culturally significant occurrence that would facilitate his audience’s receptivity to his teachings.5

The Why

Paraphrasing Hugh Nibley, Ricks observed, “One of the best means of establishing a text’s authenticity lies in examining the degree to which it accurately reflects in its smaller details the milieu from which it claims to derive.”6 The small details in Mosiah 1–6 illustrate the doctrinal and historical authenticity and richness of the Book of Mormon. Far from a warmed-over appropriation of nineteenth-century frontier revivalism,7 Benjamin’s speech deftly incorporates elements that accurately reflect many elements of ancient Israelite kingship and covenant ideology. As Ricks concluded, “That the covenant ceremonies in both the Old Testament and the book of Mosiah reflect an ancient Near Eastern pattern prescribed for such occasions may provide another control for establishing the genuineness of the Book of Mormon.”8

Additionally, the powerful emphasis Benjamin put on these specific regal themes and doctrines at his son’s coronation helps readers focus on the King of Kings and His central role in God’s eternal plan. “This sermon ranks as one of the most important in scripture,” Ricks rightly observed. “It serves to fulfill one of the primary purposes of the Book of Mormon by placing central focus and highest importance on the life, mission, atonement, and eternal reign of the heavenly King, Jesus Christ, the Lord God Omnipotent.”9

Further Reading

Stephen D. Ricks, “King, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1991), 209–219.

Stephen D. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” in King Benjamin’s Speech: “That Ye May Learn Wisdom”, ed. John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 233–276.

Book of Mormon Central, “Did Jacob Refer to Ancient Israelite Autumn Festivals?” KnoWhy 32 (February 12, 2016).

- 1. The reason for this abruptness is perhaps best explained by Royal Skousen, as reported in Michael De Groote, “Scholar’s Corner: The stolen chapters of Mosiah,” Deseret News.

- 2. Stephen D. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” in King Benjamin’s Speech: “That Ye May Learn Wisdom”, ed. John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 233.

- 3. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 233.

- 4. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 264.

- 5. Book of Mormon Central, “Did Jacob Refer To Ancient Israelite Autumn Festivals? (2 Nephi 6:4),” KnoWhy 32 (February 12, 2016).

- 6. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 264.

- 7. As argued by Grant H. Palmer, An Insider’s View of Mormon Origins (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2002), 96–99; Dan Vogel, Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2004), 153–154.

- 8. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 265.

- 9. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 265.